Nigeria’s urban landscape is filled with street names that trace back to its colonial rule, many of which honor British colonial officers with deeply oppressive legacies. These individuals played direct roles in military conquests, forced labor, and systemic racial segregation. While many countries have taken steps to decolonize their urban spaces, Nigeria remains slow in addressing the implications of these street names. This article explores how these colonial figures shaped Nigerian history and why their names still dominate public spaces.

Colonial Figures and Their Legacies

Harold Mordey Douglas – Douglas Road, Owerri, Douglas Street, Calabar

Harold Mordey Douglas served as a political officer attached to the British army during its invasion of Arochukwu and is remembered by historians as one of the most brutal and overbearing district officers in the region. His authoritarian rule, violent temper, and disregard for indigenous rights made him feared among the local communities he governed. Like many colonial officers, he viewed the native population as subjects to be controlled rather than as people with their systems of governance and cultural autonomy.

In March 1894, Mordey’s cruelty was on full display when he ordered the burning and destruction of every compound in Eziama, a community that had refused to obey his directive to construct roads. This act of collective punishment was meant to instill fear and force submission. He routinely flogged native chiefs who arrived late to meetings, using public humiliation and physical violence to reinforce colonial authority. His administration relied heavily on forced labour, where Africans were conscripted against their will to work on infrastructure projects that primarily served British economic interests.

Douglas’s acts of violence extended beyond political enforcement—he frequently inflicted brutal punishments on local people, demonstrating an unchecked abuse of power. His cruelty was not limited to governance; he fathered numerous children with local women, reflecting the imbalance of power in colonial relationships where African women were often coerced into unions with British officials.

Despite his legacy of brutality, exploitation, and unchecked colonial power, Douglas’s name still lingers in modern Nigeria. A street in Calabar and a road in Imo State continue to bear his name, serving as a reminder of how colonial figures who committed atrocities were once glorified and how Nigeria has yet to fully reckon with this past.

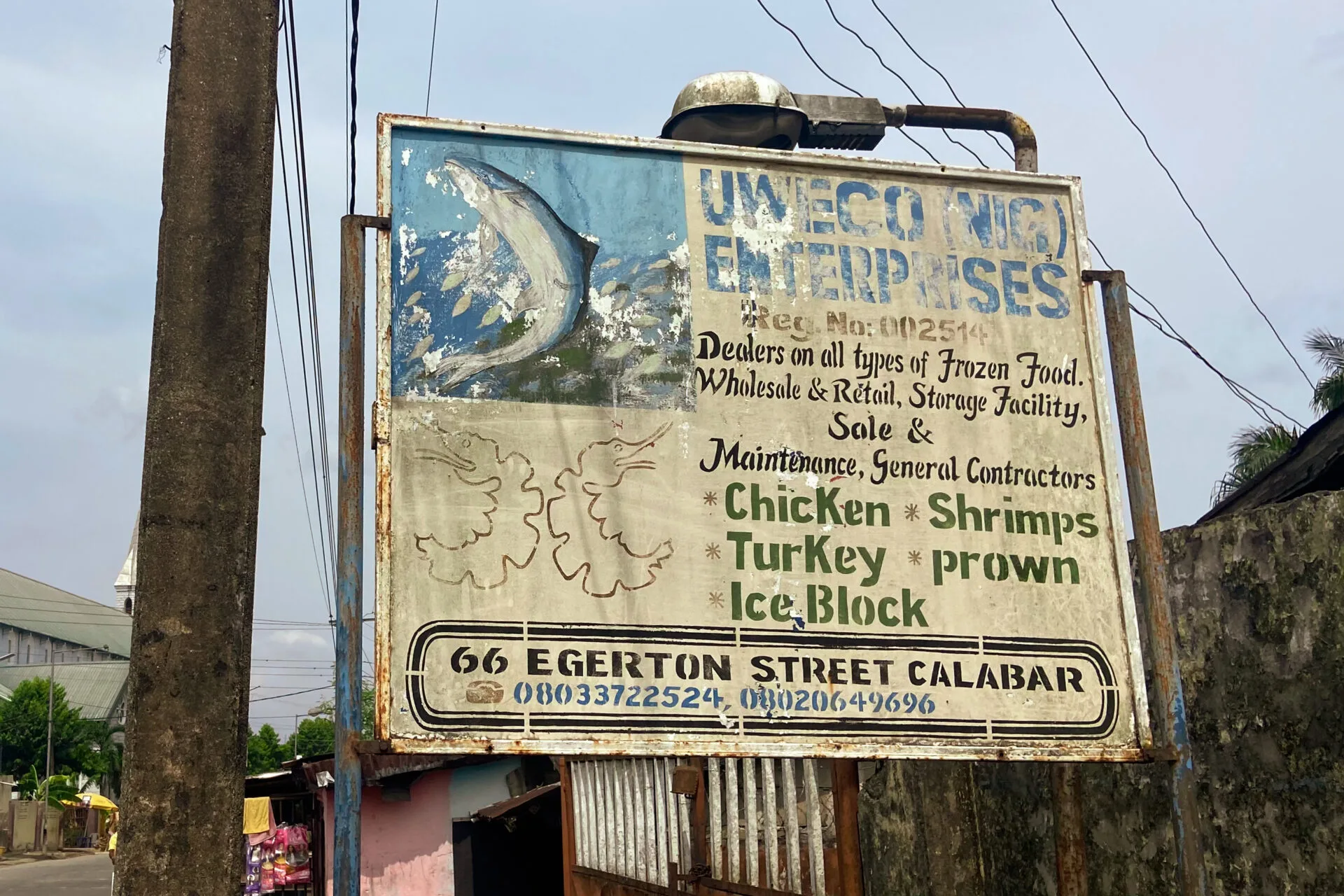

Walter Egerton – Egerton Street, Calabar

Walter Egerton was the Governor of Southern Nigeria from 1903 to 1912 and was a staunch enforcer of colonial rule. He openly encouraged his staff to avoid “undue leniency,” believing kindness could be mistaken for weakness. He also urged them to conscript as much local labor as necessary, reinforcing exploitative labor systems that placed immense burdens on the native population, and compelling them to work on colonial infrastructure projects with little to no compensation.

Egerton’s policies contributed to systemic oppression, yet his name remains on a street in Calabar, reflecting the unchallenged glorification of colonial enforcers in Nigerian urban spaces.

Walter Egerton oversaw policies that deepened exploitation and systemic oppression. A firm believer in strict governance, he openly encouraged his staff to avoid “undue leniency,” fearing that any sign of kindness might be mistaken for weakness. He also urged the widespread conscription of local labor, reinforcing the forced labor system that placed immense burdens on the native population, compelling them to work on colonial infrastructure projects with little to no compensation.

Under Egerton’s administration, the British consolidated their monopoly over trade and resources, ensuring that local economies were heavily dependent on colonial interests. He prioritized the expansion of British commercial enterprises, particularly in agriculture, pushing for increased palm oil production—a sector that generated immense wealth for Britain but offered minimal benefits to the indigenous people who cultivated it. He also presided over aggressive tax policies, further extracting wealth from Nigerian communities to finance colonial administration while offering no meaningful investment in their well-being.

Egerton’s tenure saw the violent suppression of resistance movements that sought to push back against British control. His administration maintained harsh punitive expeditions against communities that resisted colonial policies, justifying these military actions as necessary for maintaining "law and order." His governance laid the groundwork for British policies that would later entrench indirect rule, allowing colonial officials to exploit indigenous structures while maintaining their grip on power.

Despite his role in enforcing exploitative labor practices, economic subjugation, and political repression, Egerton’s name remains as a named street in Calabar, reflecting the unchallenged glorification of colonial figures in Nigerian urban spaces. His legacy is a stark reminder of how colonial enforcers, who inflicted deep and lasting damage on Nigerian society, continue to be memorialized rather than critically examined and confronted.

George Dashwood Taubman Goldie – Goldie Street, Kaduna

George Goldie played a key role in British colonialism in Nigeria through the Royal Niger Company (RNC), which engaged in fraudulent treaties, violent suppression, and economic exploitation. His company falsified agreements with indigenous leaders imposed exorbitant taxes, and banned trade with foreign and neighboring communities, ensuring total dependence on the RNC. Despite British government restrictions, the company continued implementing monopolistic policies, exploiting resources without contributing to infrastructural development. His private army, the Royal Niger Constabulary, committed atrocities, including holding children hostage and murdering Sierra Leonean laborers.

The RNC pillaged communities in its trade zone, providing no significant benefits in return. When these crimes became too severe to ignore, the British government revoked the RNC’s charter, but Goldie burned company records, erasing much of Nigeria’s early colonial history. Ironically, he later proposed Nigeria’s formation, despite his company having governed without responsibility, enriching itself at the expense of the people. His name is still honored in Kaduna and Calabar, highlighting how Nigeria has yet to fully confront its colonial past.

John Hawley Glover – Glover Road, Lagos

John Hawley Glover, a British colonial administrator and former naval officer, is best remembered for forming the Hausa Militia, a paramilitary force that reinforced British authority in Nigeria. As the governor of Lagos from 1863 to 1872, he established this militia as a strategic tool to suppress resistance, enforce colonial policies, and expand British control into the hinterlands. The Hausa Militia, composed primarily of northern recruits, laid the groundwork for Nigeria’s modern military recruitment process, which continues to exhibit regional biases first introduced during colonial rule.

Glover’s administration was marked by his divisive approach to governance, which reinforced ethnic and regional divisions to serve colonial interests. He strategically favored northern Hausa recruits for military roles, a pattern that British officials later expanded upon to strengthen indirect rule and maintain control over diverse ethnic groups. By embedding ethnicity into military structures, Glover ensured that the British could manipulate local rivalries to prevent unified resistance against colonial rule.

Beyond militarization, Glover’s policies deepened British economic and political influence in Lagos. He expanded colonial infrastructure, particularly in trade and transportation, but primarily to benefit British merchants rather than local communities. His tenure saw the growing displacement of indigenous governance structures, with British-appointed administrators taking precedence over traditional rulers. While he introduced some municipal reforms, they largely served colonial interests, ensuring that British rule remained firmly entrenched in Lagos and its surrounding regions.

Despite his role in entrenching militarized colonial control, ethnic divisions, and exploitative governance, Glover’s name is prominently featured in Lagos, with major streets and landmarks bearing his name. His legacy serves as a reminder of how colonial figures who manipulated ethnic identities for political dominance continue to be memorialized in Nigerian urban spaces, often without critical reflection on their true impact.

Ralph Moor – Moore Road, Calabar

Ralph Moor was the High Commissioner of the Southern Nigeria Protectorate and played a crucial role in Britain’s military campaigns in West Africa, particularly in the violent suppression of indigenous resistance. Before becoming High Commissioner, he served under Sir Claude Maxwell MacDonald, the Consul General of the Oil Rivers Protectorate, where he gained a reputation for his ruthless enforcement of British colonial policies.

Moor was instrumental in the invasion of Benin in 1897, a brutal campaign that saw the destruction of the Benin Kingdom, the looting of its treasures, and the forced exile of Oba Ovonramwen. His role in the Anglo-Aro War(1901–1902) further cemented his legacy as a key architect of British expansion through military aggression, leading to the destruction of Arochukwu and the dismantling of the Aro Confederacy, which had resisted British economic and political dominance.

Moor’s tenure as High Commissioner saw the intensification of forced labor, heavy taxation, and exploitative economic policies, all of which ensured that Southern Nigeria’s resources were directed toward British interests. His administration expanded the use of military force to quell dissent, reinforcing the colonial strategy of governing through violence and coercion.

Despite his contributions to British imperialism, Moor’s career ended in personal tragedy. He struggled with severe mental health issues, likely exacerbated by the weight of his brutal campaigns and the pressures of colonial administration. He ultimately committed suicide in 1909, marking a tragic end to a career defined by conquest and suppression.

Despite his role in violent colonial conquests, forced labor policies, and the destruction of indigenous governance, his name remains immortalized in Calabar’s urban map, serving as a stark reminder of how colonial enforcers, responsible for immense suffering, continue to be commemorated in Nigerian spaces without critical reassessment of their legacy.

The Lasting Impact of Colonial Street Names

The legacies of colonialists like Douglas, Egerton, Goldie, Glover, and Moor continue to shape modern Nigerian society. Their actions contributed to deep-seated structural issues that persist today, including:

Social and Economic Inequalities

Colonial policies entrenched a rigid class system, creating disparities between urban and rural areas. Even today, access to education and economic opportunities often follows patterns established during colonial rule, perpetuating inequality.

Cultural Erosion

British colonialists imposed Western values and institutions, disrupting indigenous governance, religious practices, and social structures. The presence of their names in Nigerian cities serves as a continuous reminder of cultural displacement.

Political and Governance Challenges

Nigeria still grapples with the consequences of colonial rule in governance and national identity. Ethnic and religious conflicts have roots in colonial strategies of divide and rule, with these tensions influencing modern politics.

Economic Underdevelopment

The extraction-based economy established by British rule prioritized resource exploitation over sustainable development. This colonial economic model contributed to Nigeria’s ongoing struggle with diversification, poverty cycles, and underdevelopment.

Ikoyi Reservation in Lagos

Ikoyi was designated as a European residential area in 1919, symbolizing colonial racial segregation. Streets such as Osborne and Bourdillon still reflect the prestige and power of whiteness in Nigeria’s urban planning.

Colonial Mentality and Urban Nomenclature

British colonialists renamed cities and neighborhoods to reflect European dominance. Port Harcourt, for example, was named after a British official, reinforcing a colonial narrative that persists in Nigerian urban centers.

Resistance to Renaming Streets

While some countries have successfully renamed streets to reflect post-colonial identities, Nigeria has been hesitant to do the same. Lagos lawmakers, for instance, voted against renaming streets named after colonial masters, indicating a reluctance to challenge colonial legacies.

The names of colonial streets in Lagos have significantly influenced the city’s cultural identity by embedding a complex legacy of colonialism, resistance, and hybridization:

Colonial Legacy and Power Dynamics

Streets named after British officials, such as those in Ikoyi (e.g., Bourdillon and Alexander), symbolize colonial dominance and remind Lagosians of the power structures imposed during British rule. These names often overshadow indigenous contributions to the city’s development.

Preservation of Indigenous Identity

Despite colonial influences, many streets retained Yoruba names, reflecting a bilingual and hybridized cultural identity. This preservation of Indigenous names challenged the erasure of local languages and traditions, showcasing the resilience of Lagosians in maintaining their cultural heritage.

Cultural Conflict and Transformation

The coexistence of European and Yoruba street names highlights a cultural conflict where Western emulation influenced urban identity while simultaneously leading to the loss of some indigenous traditions. However, it also created a unique socio-linguistic environment where pidgin English and Yoruba coexisted with English.

Calls for Renaming

Efforts to rename streets after Nigerian nationalists and historical figures aim to reclaim cultural identity and educate future generations about Nigeria’s history, fostering pride in Indigenous contributions. Overall, colonial street names in Lagos serve as markers of historical memory, blending colonial imposition with indigenous resilience.

ChallawaRiver Homes embraces indigenous heritage by naming its Suites and celebrating local culture rather than glorifying colonial figures. By honoring Nigerian history and traditions, ChallawaRiver Homes provides a meaningful alternative to the colonial imprints still visible in Nigeria’s urban planning. This approach fosters cultural pride and challenges the lingering effects of colonialism, proving that decolonization begins with intentional choices in how we name and shape our spaces.