Echoes of a Glorious Past

Before colonial powers carved borders across West Africa, the Kingdom of Calabar, known to its people as Akwa Akpa, meaning “Big River” in Efik, stood as one of the continent’s most sophisticated societies. Nestled at the meeting point of the Calabar and Cross Rivers, this city-state was perfectly positioned for trade, diplomacy, and cultural exchange.

Home to the Efik, Efut, and Qua (Ejagham) communities, each with distinct traditions and governance systems, Calabar thrived as a hub of political order, spiritual depth, and artistic expression. Though later renamed by Portuguese and Spanish explorers, the spirit of Akwa Akpa still echoes through its people, rituals, and riverside architecture.

In 1976, during a state creation exercise under General Murtala Mohammed's regime, the region formerly known as the South-Eastern State was renamed Cross River State. Despite these changes, the spirit of Akwa Akpa endures in its people's traditions, architecture, and rituals.

Now, let’s uncover 7 fascinating truths about this remarkable kingdom before colonial rule reshaped its legacy.

A Political System Rooted in Order and Wisdom

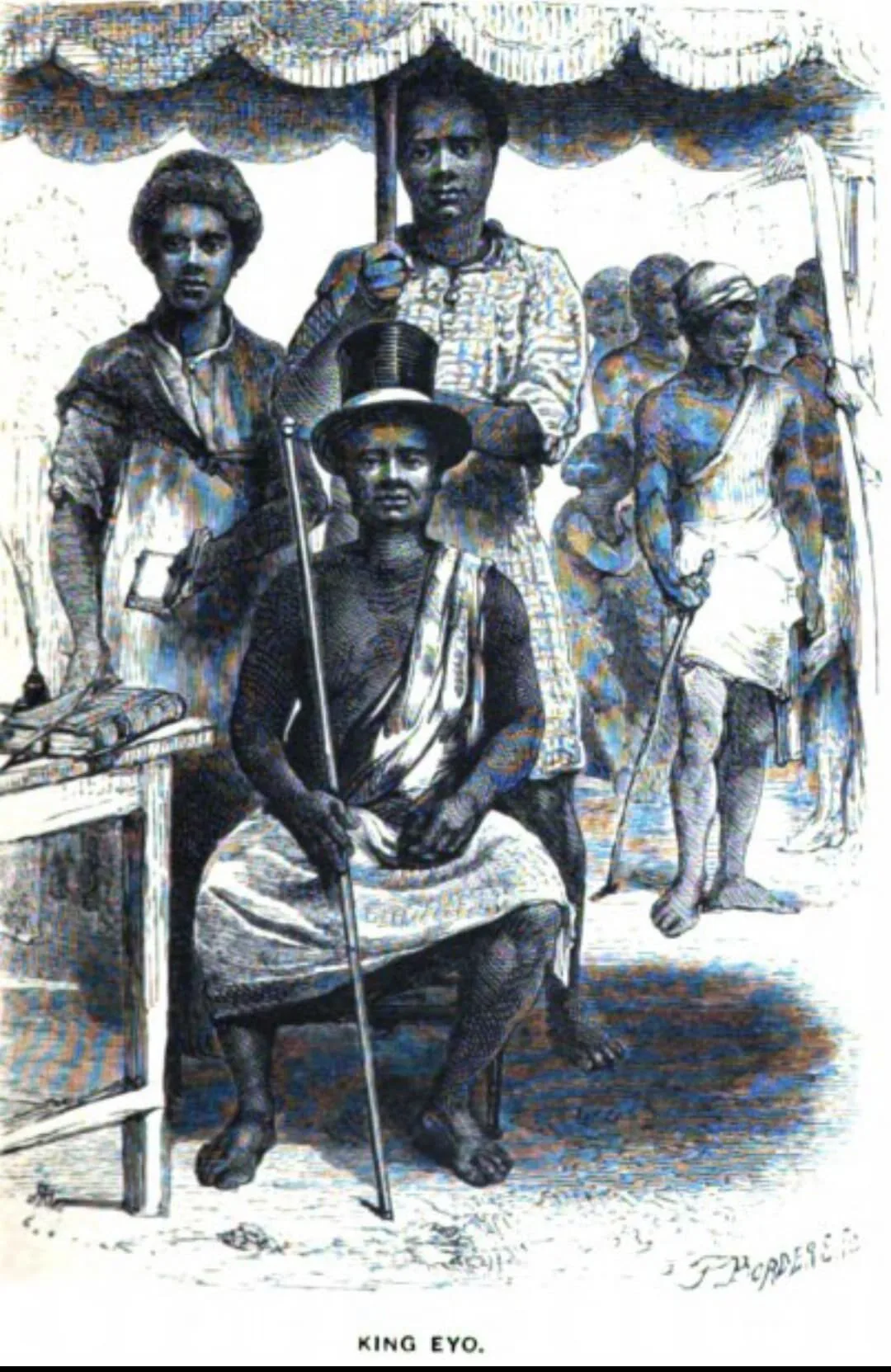

Long before Western democracy took root, the Efik people of Calabar had their own structured governance. At the helm was the Obong of Calabar, a king chosen through noble consensus and spiritual rites. Beneath him, the Ekpe society operated like a judicial and legislative council, ensuring order and enforcing laws. This secret society wasn’t just a brotherhood, it was a political institution, with coded communication, hierarchical ranks, and real civic power. The system functioned like a checks-and-balances structure, centuries before it became standard in modern governance.

However, Calabar was never a one-crown show. The city was historically governed by three major kingdoms, each with its monarch, traditions, and domain of influence:

The Efik kingdom, led by the Obong of Calabar, was the most politically dominant, thanks to its strategic control of river trade routes and its expertise in international diplomacy.

The Efut, guided by the Muri Munene, were deeply spiritual people whose governance was rooted in forest mysticism and sacred traditions.

The Qua (Ejagham), under the leadership of the Ndidem, held sway over the inland territories and were celebrated for their oral storytelling, artistry, and craftsmanship.

Though politically distinct, these kingdoms were far from isolated. Through intermarriages, shared festivals, joint spiritual practices, and mutual participation in institutions like the Ekpe society, they functioned in a web of interdependence, each contributing to a dynamic triune political force in the region. This unique configuration created a harmonious balance of power that promoted both unity and autonomy within the broader Calabar polity.

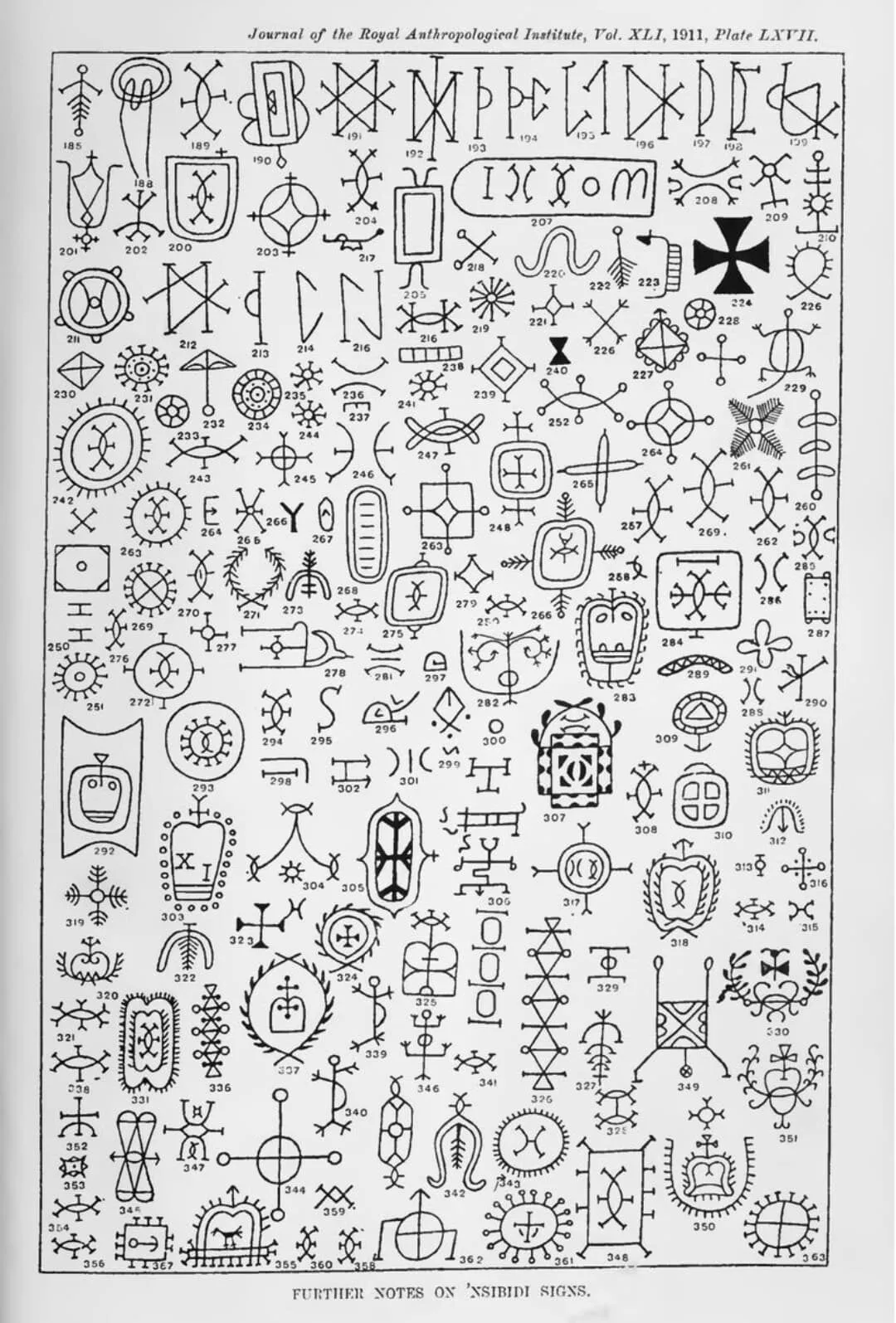

Nsibidi: Africa’s Ancient Written Code

While many histories claim Africa lacked writing before colonialism, Calabar tells a different story. The Efik and their neighbors used Nsibidi, a sophisticated symbolic writing system dating back over a thousand years. Nsibidi wasn’t phonetic like English but ideographic, each symbol carried deep meaning. It was carved on walls, drawn on cloth, and even danced in the air during masquerades. Used in everything from love letters to court records, Nsibidi was the ancient Google Docs of the Cross River region

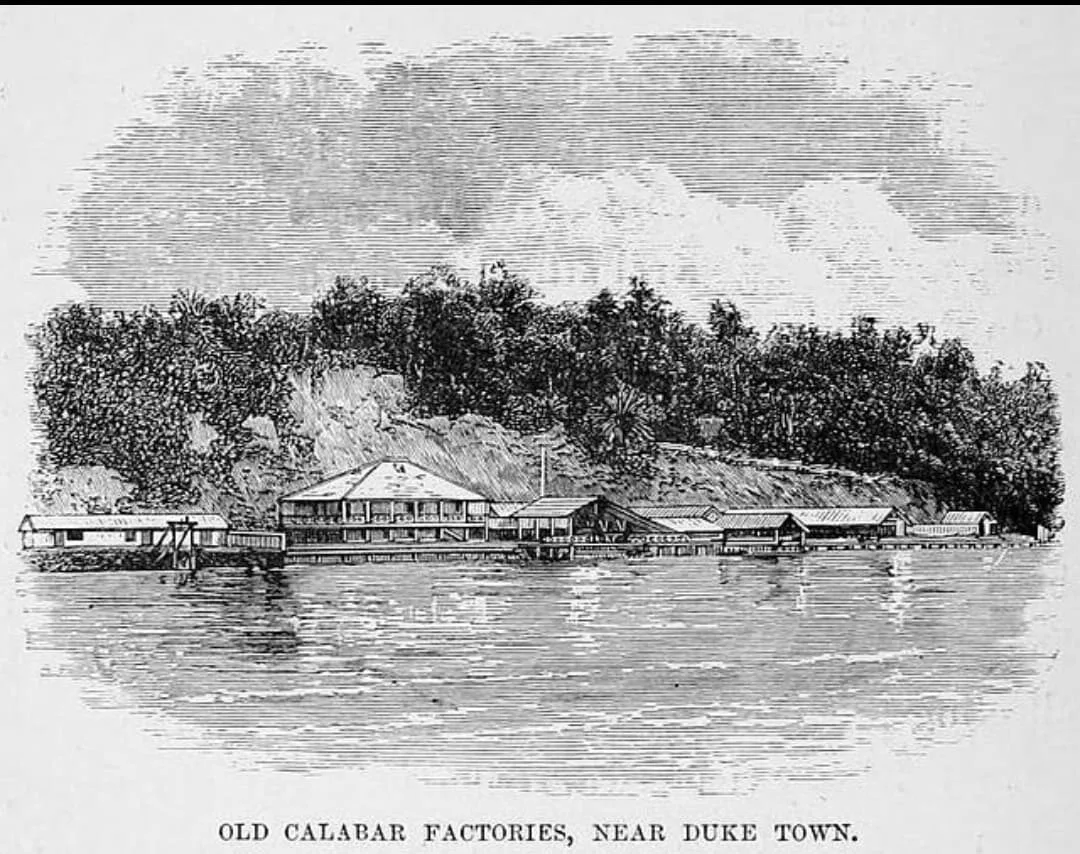

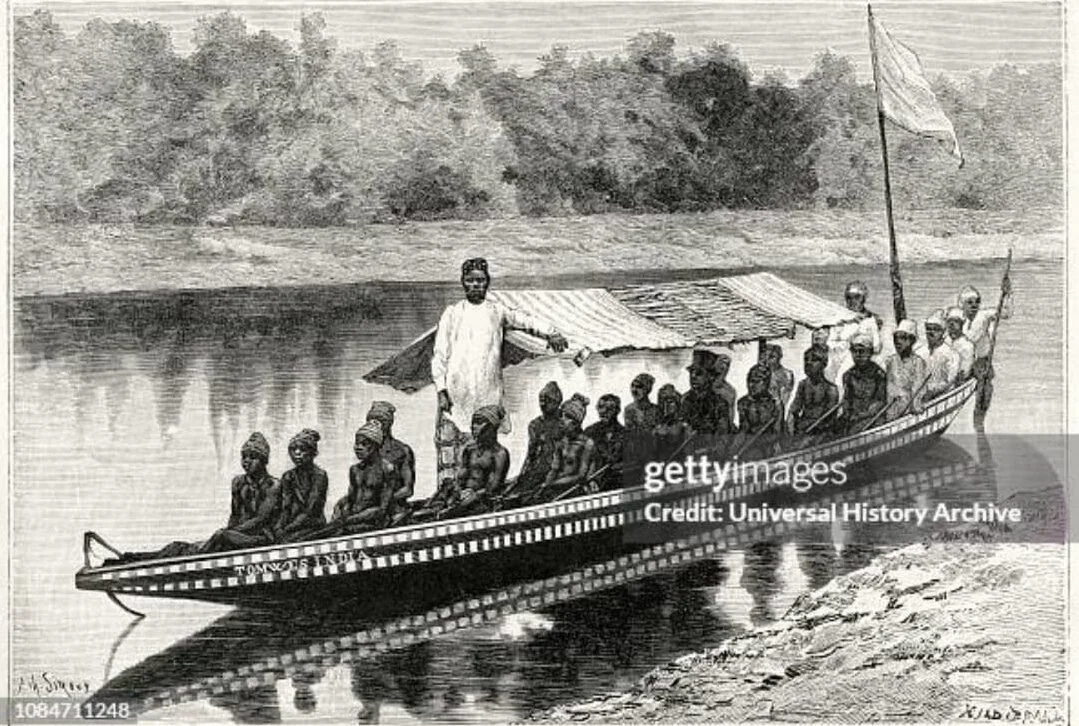

A Thriving Global Trade Economy

Calabar's strategic location along navigable rivers and proximity to the coast made it a global trade powerhouse. The Portuguese were among the first Europeans to arrive in the 15th century, naming the area "Calabar". The Dutch followed in the 17th century, establishing trading posts and competing with the Portuguese for control over the lucrative slave trade. The British later became dominant, with merchants from Liverpool, London, and Bristol engaging extensively in trade activities in Old Calabar.

Efik middlemen controlled river trade routes, negotiating favourable deals that ensured wealth flowed into the kingdom. At its peak, Calabar rivaled any European port city in activity and commercial influence.

A Culture of Fashion, Class, and Identity

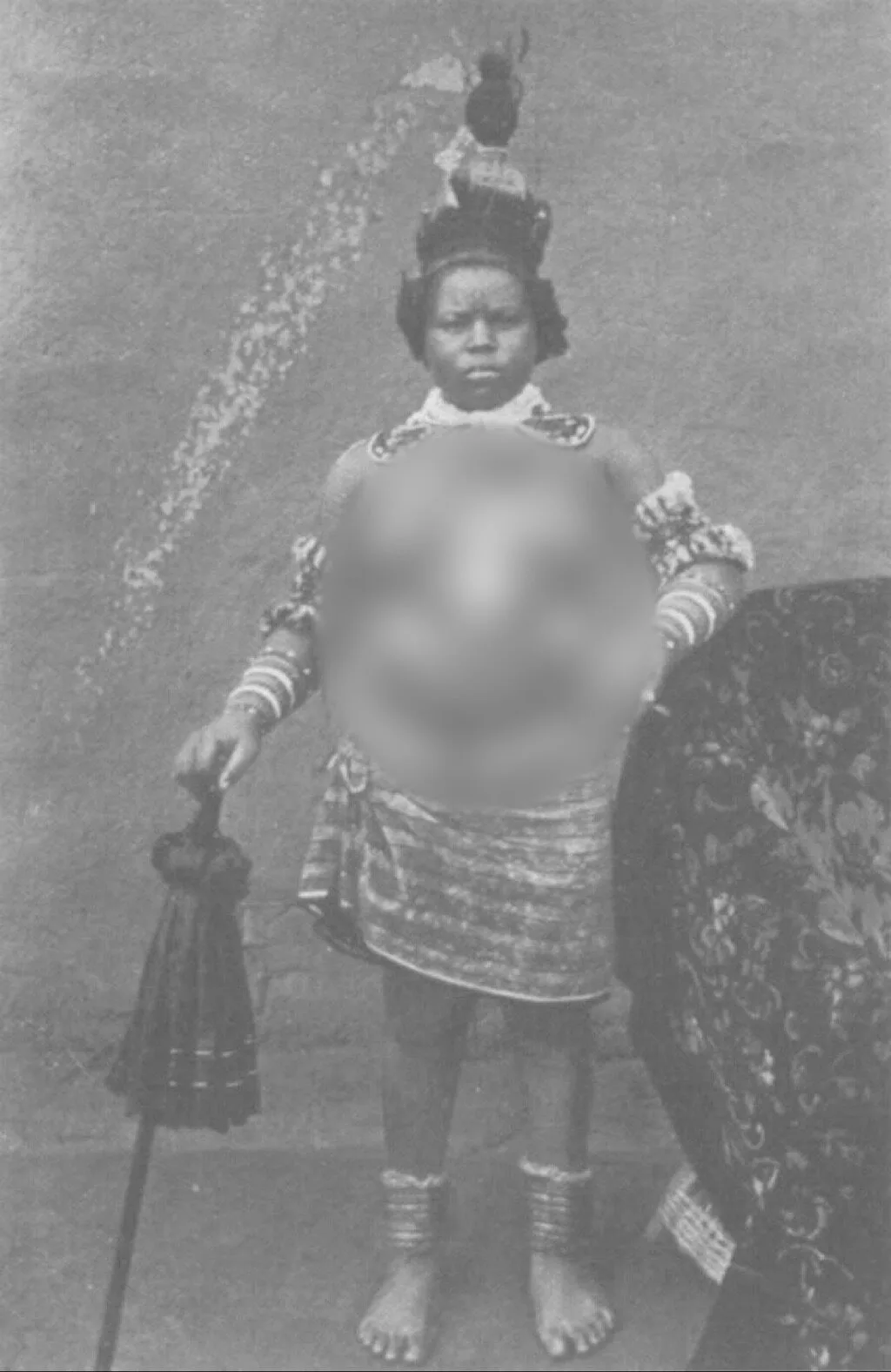

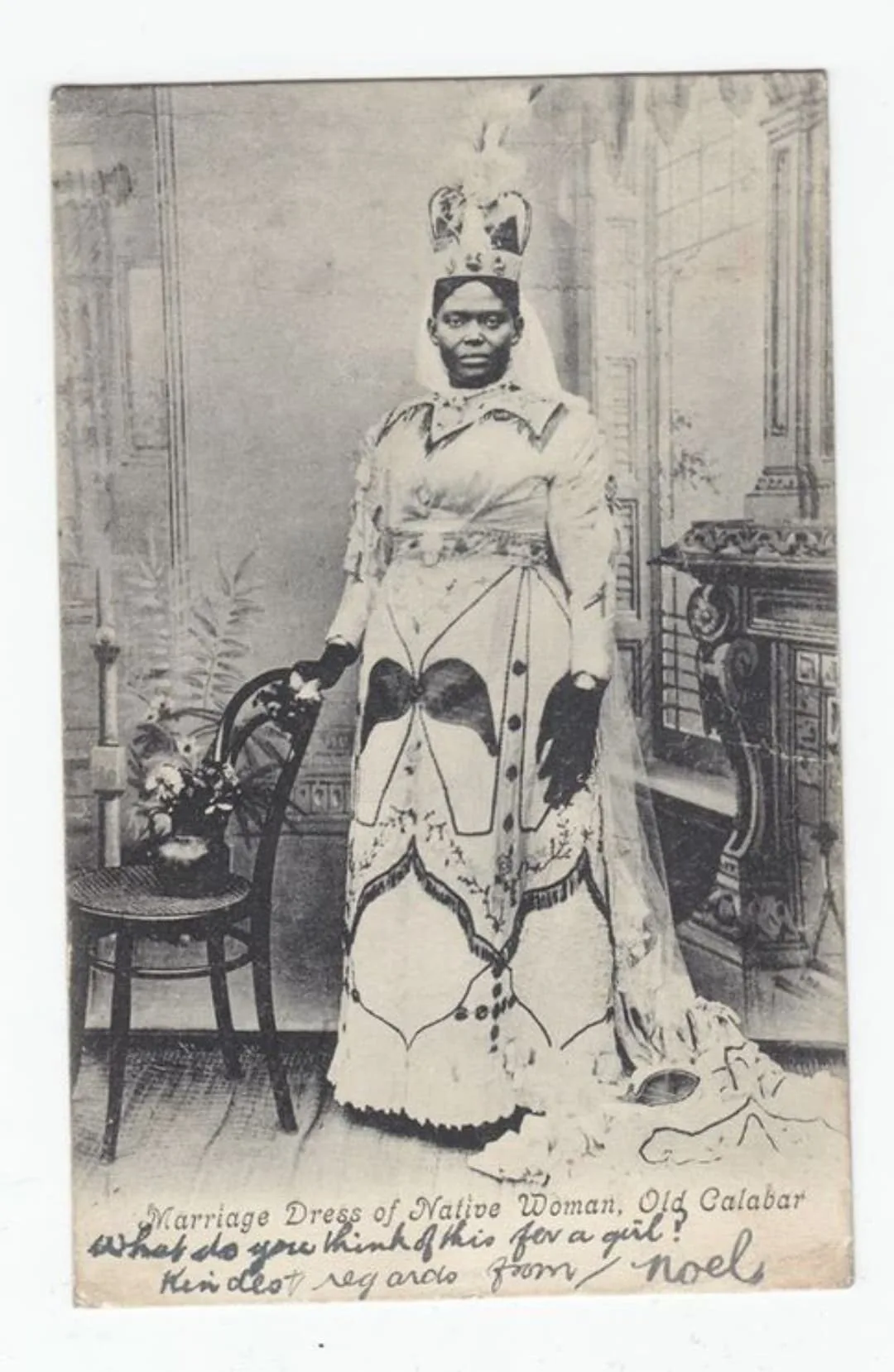

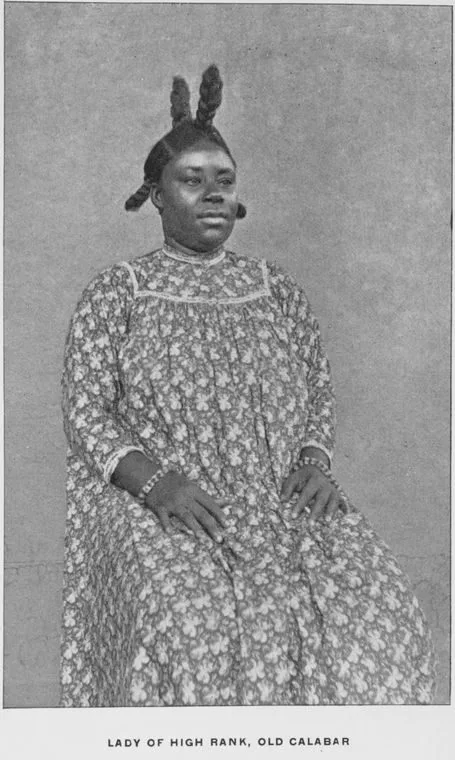

In precolonial Calabar, fashion was more than aesthetics. It was a declaration of power and identity. Efik women wore intricately wrapped wrappers made from imported fabrics, often paired with coral bead necklaces and chalk body markings that symbolized purity or status. Men donned embroidered tunics, often with brass armlets and carved staffs.

Women in ancient Calabar, particularly among the Efik people, traditionally wore attire made from raffia known as Ikpaya, which included a skirt-like wrapper and a tunic. They also adorned themselves with various anklets such as heavy brass ones (Ewọk), ivory anklets (Mme) for wealthy women, and special anklets for ceremonies like marriage (Ndañ). Necklaces were also common, with different types of signifying status or occasion. Hairstyles were distinctive, often styled tightly into a cone shape above the crown, giving a dignified appearance. With missionary influence from 1846, Victorian-style dresses called Onyonyo and their variants were introduced.

Spirituality as a Way of Life

Religion was integral to Calabar's society. The Efik people revered Abasi Ibom, the Supreme Creator, and honored a pantheon of deities and ancestral spirits. Sacred groves served as natural cathedrals for rituals and offerings. The Ekpe society blended political authority with spiritual duties, ensuring that major decisions were guided by divine will.

One of the most revered deities in Efik mythology is Anansa, the goddess of the river and beauty. Believed to embody the spirit of the Calabar River, Anansa influences fertility, prosperity, and artistic inspiration. The traditional Ekombi dance, characterized by graceful and fluid movements, is performed to honor her, with tales suggesting that the dance comes naturally to those chosen by Anansa.

At ChallawaRiver Homes, we honor this rich cultural heritage through our thoughtfully designed spaces. Our Anansa Suite, inspired by the revered folklore river goddess, offers a premium retreat blending modern comfort with traditional Efik aesthetics. Each detail, from locally produced artwork to intricate furnishings, celebrates the vibrant culture and rich heritage of the Efik people. Visit us today and discover a home that connects you to the soul of Calabar.

Storytelling, Proverbs, and Oral Philosophy

While much of Africa's wisdom was passed down orally, Calabar made an art of it. The Efik were master storytellers, preserving philosophy, history, and values through proverbs, fables, and praise poetry. In moonlit village squares, elders recited tales that carried coded lessons about leadership, greed, unity, and love. A single proverb could settle a dispute or advise a king. One popular saying goes: “When the drum changes its beat, the dance must change as well”—a poetic call for adaptation and wisdom in changing times.

Women Were Powerful Keepers of Tradition

Contrary to colonial assumptions, Efik women held significant power in precolonial Calabar. They were far from passive bystanders—they were traders, spiritual leaders, cultural custodians, and even participants in secret societies like ‘ekpo ndem isong’ the revered women’s spiritual guild. In the bustling marketplaces of Akwa Akpa, women ran the economy with unmatched prowess, negotiating prices, managing trade networks, and securing wealth for their households and clans.

Within the family, Adiaha, the first daughter was a figure of authority, holding ceremonial responsibilities and being regularly consulted on key family matters.

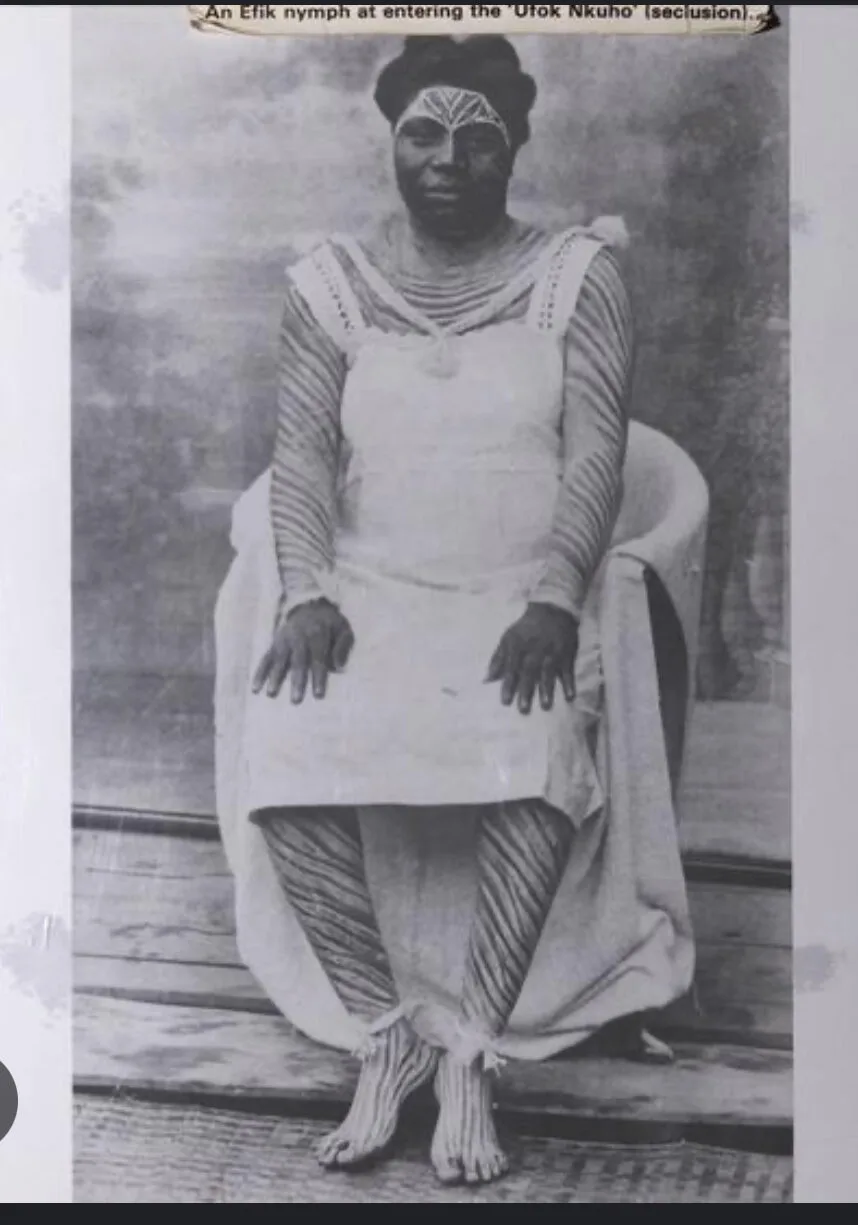

One of the most iconic expressions of female identity in Efik culture was the Fattening Room or Nkuho. This sacred rite of passage was reserved for maidens of acceptable age, usually sent by their fathers who had paid the necessary sum for coral beads and made offerings to appease Nku, the revered river goddess. Participation in the Nkuho was considered proof of chastity and a sign of noble upbringing.

Once admitted, the young women were kept in strict seclusion for about a month, isolated from society, and not allowed to receive visitors except for a few trusted elderly women who served as caretakers and instructors. During this time, the girls were pampered with nourishing meals meant to increase their body size, as plumpness was considered a symbol of beauty, fertility, and affluence. Meals were often hand-fed, regardless of the maiden's appetite, which made the experience demanding for some.

In addition to dietary indulgence, they were given beauty treatments, and body massages with traditional oils, and taught essential skills such as domestic arts, sensuality, spiritual responsibilities, and social etiquette. This training prepared them not just for marriage, but for a dignified womanhood within the Efik society. Toward the end of the seclusion period, the girls were traditionally circumcised by their mothers, a deeply personal and symbolic act, often considered a final step into adulthood.

After healing and completing their training, the maidens were presented to the community in a grand public ceremony. Friends, family, and potential suitors would gather to witness their emergence. They danced elegantly to traditional rhythms, adorned in coral beads and wrappers, displaying their enhanced figures and graceful poise—living proof of their transition from girlhood to womanhood.

Far from being just a beauty ritual, Nkuho was a powerful symbol of feminine wisdom, societal respect, and holistic preparation for adult life, reinforcing the central role women played in the resilience and continuity of Efik society.

A Kingdom Worth Remembering

The Kingdom of Calabar before colonial rule was no untamed frontier. It was a flourishing civilization guided by its compass of culture, language, law, art, and spirit. Its people were masterful traders, guardians of deep ancestral wisdom, and artisans of enduring beauty. As modern Calabar evolves, it rises upon these ancient legacies that deserve not just remembrance, but reverence. To explore this regal past is not merely an act of historical curiosity, but a reclamation of identity, pride, and belonging.

At ChallawaRiver Homes, we pay homage to this rich cultural heritage through our thoughtful interior decor, curated art pieces, and the ambiance we create. Each space whispers a story of the past, inviting you to experience both nostalgia and history in one elegant breath. Visit us today and discover a home that doesn't just shelter you—but connects you to the soul of Calabar.